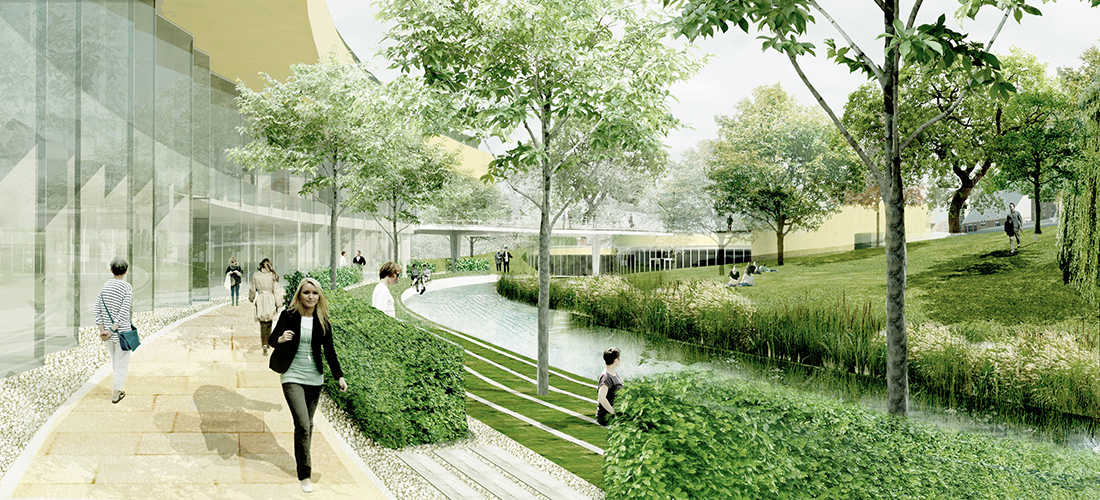

The inclusive planning process led to increased focus on social and ecological sustainability on Campus Albano, now under construction.

Credit: Stadsbyggnadskontoret Stockholm (The Stockholm City Planning Office).

Looking at the planning process design as a critical element of the Campus Albano project can provide valuable insights to others who are or will be working with similar inclusive and integrated design processes. The campus, which currently is under construction, is located in the Stockholm National Urban Park, the world’s first urban national park. The location strongly dictated the campus development project’s design demands, limitations, and potential. The aim was to design the campus so as to support social and ecological values in an integrated fashion (i.e. social-ecological urban design), and to better connect Stockholm’s main institutions of higher education: Stockholm University, Karolinska Institute, and the KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

The Campus Albano planning constituted of two processes: the formal process, and a self-organized parallel process. After a first campus design proposal had been presented and rejected, the city architect was given the task of designing the campus. The city architect formed a network of architects and other experts, as well as representatives from the municipality and county board, with the intention of assuring that the campus design followed protocol.

During that time, beginning in September of 2009, urban resilience and sustainability researchers, designers and architects formed the Patchwork group with the aim to create an alternative vision for the new campus. This self-organized process offered some novel contributions to the design of the planning process and of the campus: a) the inclusion of researchers, interest groups, and civil society concerned with the Stockholm National Urban Park, and b) the focus on social and ecological integration not only in the appearance and functions of the Campus, but also in the design, research, and management processes. The resultant alternative vision won the support from the real estate owners, the University, the City, and interest organizations focused on protecting the Park.

Collaborations and conflicts

The city architect and the Patchwork group met in several meetings and workshops, as part of the process of integrating the Patchwork group’s design vision, called the Albano Resilient Campus, with the city architect’s preparation of the official zoning plan proposal. Although both parties recognized the importance of the project and the focus on sustainability, conflicts arose.

Interviews with key stakeholders show that the city architect had the vision of creating a campus that blended in with the natural landscape. However, the city architect’s building design was perceived by the Patchwork group members as dominant, and a disruption of the landscape. The design stopped short at focusing on the built-up landscape instead of incorporating sustainability aspects at a deeper level such as supporting ecological processes, encouraging meetings between users, and including local stakeholders in the long-term management of the campus.

The societal actors working with the Patchwork group in developing the alternative campus vision perceived the collaboration with the researchers as adding a deeper understanding of sustainability. However, the city architect did not share this sentiment; conflicts built up between the two distinct visions for the campus, and culminated in one of the Patchwork group members being told to leave the process.

Eventually, the alternative vision was partially incorporated into the zoning plan proposal, and the plan was first approved in 2012. It was appealed but finally approved in 2015. The final plan included significantly more social and ecological sustainability dimensions than the original plan, such as urban gardens, wetlands, and redesigned waterways, more attention to the functionality of the built-up landscape, and incentives for involving different groups in the long-term management of the green spaces. However, the zoning plan remains a scaled-down version of the alternative vision developed by the Patchwork group.

Reflections

The obvious question is: why did a conflict arise? The Campus Albano experience shows that the concept of sustainability can be interpreted in fundamentally different ways. It also shows that formal power structures can be the determining factor for the outcome even in a collaborative process. The latter points to the importance of the key elements in each collaborative process. In the case of Campus Albano, an experienced and well-respected city architect was entrusted the important and complicated task to fulfil the goal of designing a new state-of-the-art campus, and had no formal obligation to follow anyone else’s guidelines. That context can either invoke increased will to collaborate, or a firmer will to stick to one’s own skills and opinions.

The city architect received input from a large number of different actors, including but not limited to that of the Patchwork group. The Patchwork group’s task was self-appointed, aiming to ensure that the new campus became as sustainable as possible in the word’s widest and most complex sense. The different objectives, networks, and status in the formal power structure may help to explain why conflicts arose in a situation where the actors involved seemingly should have collaborated towards achieving the same goal.

Some of the insights from reflecting on the process afterwards include: although initially not a collaborative planning process to the extent it became with the involvement of the Patchwork group, the group’s involvement significantly improved the Campus Albano’s sustainability profile. The process could presumably have benefited from a clear statement from the project owners, the City of Stockholm, of the importance of making social and ecological sustainability the core of the project instead of a limited add-on, and guidelines to what the concept would imply. The case also shows on how dialogues across stakeholder groups such as sustainability scientists and architects can enhance a project outcome, and that the inclusion should begin already at an early stage. Finally, it also shows that self-organized processes that are not constrained by formal regulations can help spur inspiration, encourage engagement, and lead to new solutions, which can be a valuable complement to the formal processes.

The end of one process, the rise of another

In the end, Campus Albano was developed through integrated planning and design that involved not only urban planners but also interest organizations and researchers. The process gave rise to a new emerging research and urban planning and design paradigm: Social-Ecological Urbanism.

As for Campus Albano, the multi-stakeholder involvement continues. Since production of the new campus commenced in 2015, a monitoring group has formed constituting of some of the people who were involved in the Patchwork group and its network. This new group monitors the campus development process with the aim of making the final campus design correspond as much as possible to the alternative vision originally created by the Patchwork group.

By Maria Schewenius

Thank you to Johan Colding, Stephan Barthel, Erik Andersson, and Rawaf al Rawaf for proofreading the text.